50 Years of Anti-Nuclear Mass: An Oral History

On a sunny morning last September, a small group of men and women met in the Christmas Tree Shops parking lot by the Sagamore Bridge. It was Labor Day, the unofficial end of summer, and the line of cars heading over the bridge out of Cape Cod was steadily growing as the minutes went by.

Two women from Cape Downwinders, the local anti-nuclear group that organized the day’s rally, began to unpack signs and banners from a car. They carried them over to the metal guardrail that separates the parking lot from Route 6. Nearby, Diane Turco, director of Cape Downwinders, struggled with a white pop-up tent. As she fought against the wind to tape the banners to the lightweight metal frame, the two other women, Mary Conathan and Susan Carpenter, put down their banners on the grass and came to help her.

All three wore neon green T-shirts that read “Shut Down Pilgrim” and laughed as they tried to keep the tent from blowing away. After finally getting it strapped to the guardrail with bungee cords, they walked back to the car to get the rest of their signs and greet the latest arrivals.

In all, about a dozen people came to the rally — a smaller crowd than the organizers had hoped for — and they spread out along the road with their banners and signs. Cars began honking almost immediately. Occasionally, someone rolled down a window and cheered.

“I am amazed now how many people are paying attention,” Carpenter said. Up until a few years ago, she explained, a lot of people in the area supported the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station. “People were saying that we need the power and it keeps our rates down. Now people thank us.”

For those on the Cape, the Pilgrim question is hard to ignore — and not only because of regular public demonstrations like the annual Labor Day and Memorial Day rallies at the bridge. Massachusetts’ sole nuclear power plant has been in the news for several problems, including during the most recent winter storms.

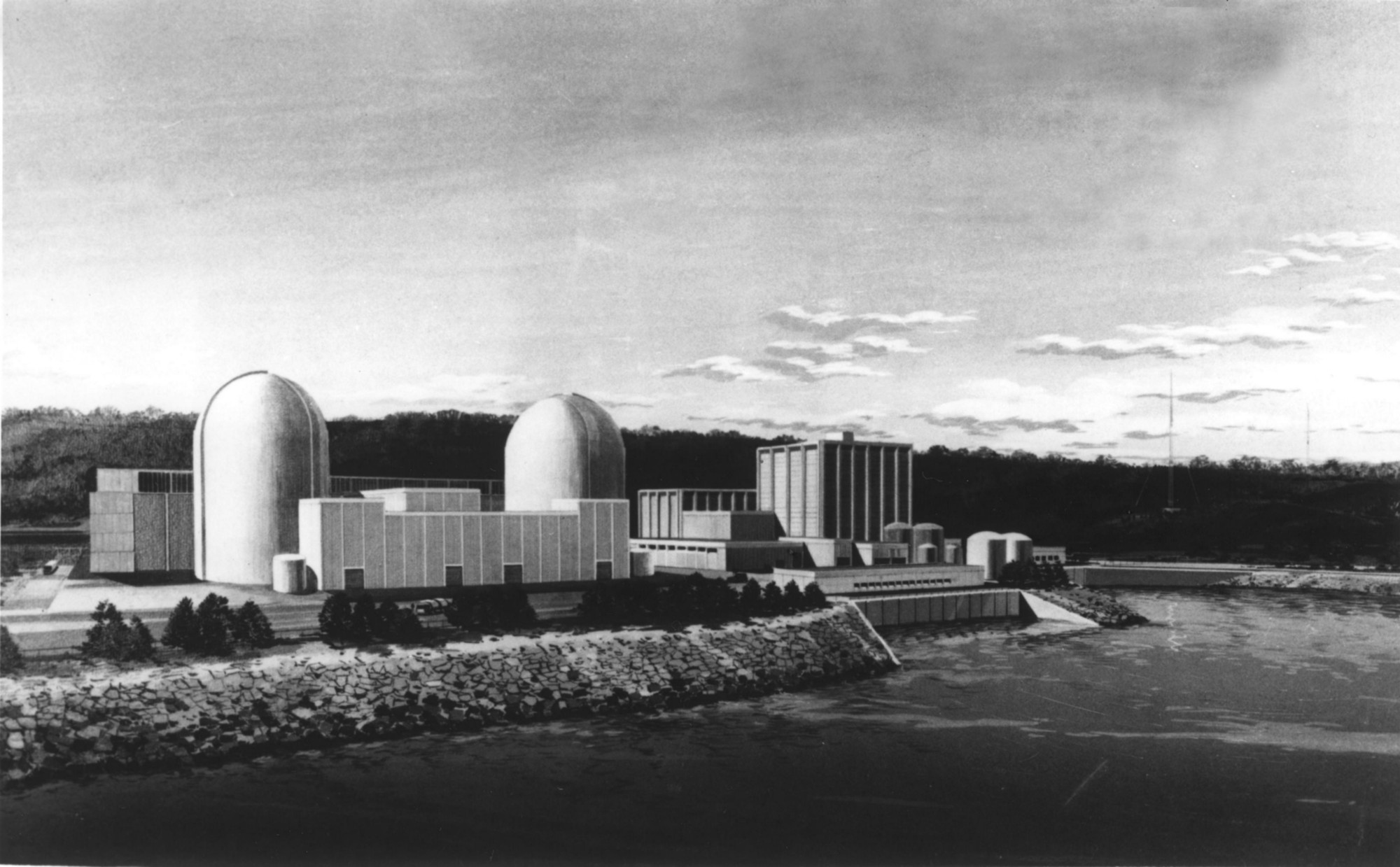

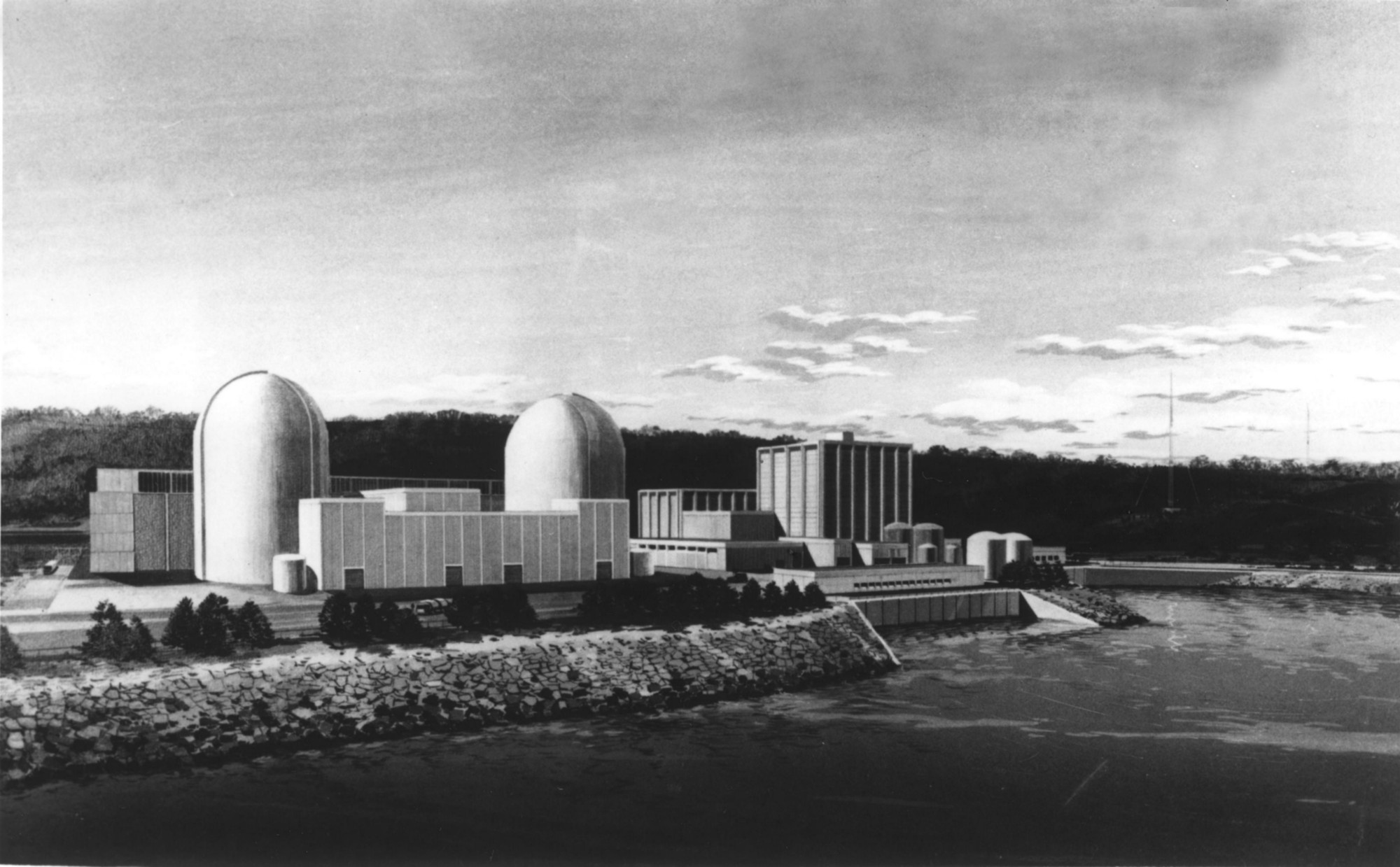

In 2015, after a series of unplanned shutdowns, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission downgraded the Plymouth plant’s safety rating and deemed it one of the three worst-performing reactors in the country. Shortly thereafter, Pilgrim’s owner-operator, Louisiana-based Entergy Corporation, announced that it would close the plant by June 2019.

For those at the bridge, the upcoming closure, while exciting, also presents a whole new host of safety concerns.

“What happens at Pilgrim could set precedent for the country, and we’re pushing for Pilgrim to be the poster child for public safety,” Turco said. “Unfortunately, we have a lot more work to do. We hope that we’ve provided a foundation for activism in our community, but this is going to be an ongoing issue.”

With the plant about to enter its final year of operation, and anti-Pilgrim activists planning the next stages of their campaign, it seemed a fitting time to look back at the 50-year fight against one of the country’s most problematic nuclear power plants.

Miriam Wasser

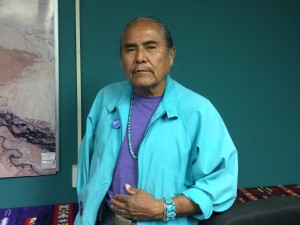

What follows is an oral history of the anti-Pilgrim movement, patched together from extensive interviews conducted with more than 20 experts and activists, many of whom have spent countless hours litigating in court, writing petitions, attending demonstrations, and even sitting in jail cells. The message, tactics, politics, and players have changed over the past half-century, but the underlying effort — to stand up for the health and safety of their families and neighbors — has been unrelenting.

READ THE INTRODUCTION AND PART I…

READ PART II…

READ PART III AND THE EPILOGUE…

CHECK OUT THE EXTRAS…

FROM THE EDITOR’S NOTE:

When we first asked Miriam Wasser to consider documenting stories about nuclear protests for our BINJ oral history series, several things were different than they are today. For one, it was before an inspector from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) accidentally forwarded a troubling report about the Plymouth plant to longtime crusader Diane Turco, executive director of the anti-Pilgrim group Cape Downwinders; among other damning statements, the email, sent on Dec 6, 2016, noted, “The plant seems overwhelmed by just trying to run the station,” and, “It appears that many staff across the site may not have the standards to know what ‘good’ actually is.” In the time since, as Miriam has spent innumerable hours researching old documents and interviewing people who have been vocally concerned about such risks for generations, its track record of safety problems has continued. During this year’s early January “bomb cyclone” that flooded much of coastal Massachusetts, the plant was forced to shut down after losing one of two external power sources.

Though the NRC appears to be an even bigger joke under President Donald Trump than it was under his negligent predecessors, the intention of this work is not to frighten readers. Rather it is to further alert the public to the bankrupt nature of what passes for real oversight in the United States, even when the lives of millions are potentially in danger. On the strength of Miriam’s hard work and expertise, and of participants who lent their memories and photos to the effort, we hope this time capsule preserves the people’s history and informs this and other movements moving forward. As is explained in detail in this volume, if not for the actions of a dedicated core activist crew on the Cape over a 50-year span, there could be two or three reactors on the bay that may have operated long after the planned closing for next year.

On that note… Pilgrim may be slated to shut down in 2019, but as the struggle chugs along for those who will still live in close proximity to possible contamination from its remnants, there’s no doubt that the forces who have stood up for their health and safety for the past half-century will keep fighting. This is their story.

Chris Faraone, BINJ Editorial Director